From moonscapes to emerald hills: How the Santa Monica Mountains recover from wildfires

Emergency aerial vehicles drop loads of water on the scorching Easy Fire on Wednesday, Oct. 30, 2019, in Simi Valley, Calif. Photo credit: Evan Reinhardt

February 19, 2020

In November 2018, the Woolsey fire ripped through Southern California and burned over 150 square miles. Over 1600 structures were destroyed and 88% of the acres owned by the National Park Service in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation area burned. Close to a year after the Woolsey Fire’s devastation, the Easy Fire burned over 1,800 acres of Simi Valley which fall within the same ecological zone.

Saturday, Feb. 15, the Santa Monica Mountains Visitor Center held a presentation where National Park Service Fire Ecologist Marti Witter discussed the conditions contributing to wildfires, how native plants normally recover after wildfires, as well as how the increasing frequency of wildfires is affecting these plants.

As for why so many fires tend to break out in the Santa Monica Mountains in general, Witter pointed to the vegetation and climate local to the area, stating “We have perfect conditions for fires.”

In terms of vegetation, Witter explained why the area is so extremely at risk.

“The vegetation of the Santa Monica Mountains, probably 75% of it is shrubland, chaparral, coastal sage scrub,” Witter said. “They couldn’t be better for igniting and carrying a fire.”

Witter elaborated that a large portion of shrubland tends to produce small, dead, dry twigs that function perfectly as kindling. Moreover, Witter continued, the shrubland in the Santa Monica Mountains has a great deal of continuity to it, which allows the fires to catch and carry quickly without interruptions.

As for climate, Witter explained the Santa Monica Mountains receive most of their rain from November through February, which leaves an extended dry period from March throughout October. This period allows plants to dry out over the summer and early fall. Then, at the same point when the native foliage tends to be at its driest, the Santa Ana winds come roaring through the area.

“So, if you get these Santa Ana events, low humidity, high winds, high temperatures and you get an ignition, then these fires take off and unless someone is very, very lucky, they become large wildfires that you can’t really do anything about,” Witter explained. “They’re wind-driven, you basically can’t control them. And they stop when they reach the ocean or the weather turns.”

Witter then discussed how the native foliage recovers after a fire.

In general, according to the National Park Service, the shrublands of the Santa Monica Mountains are adapted to the massive, incinerating wildfires that periodically tear through the area, and can recover given time. Witter explained that native shrubs can be considered seeders, sprouters or mixed.

Seeder plants are killed by the fire, but have large seed banks that sprout into new plants after the fire. Sprouters, on the other hand, keep part of themselves alive underneath the soil, which the full shrub regrows from after the fire. Finally, mixed plants use a mix of both strategies to replenish their populations.

After the presentation, Santa Monica Mountains recreational park guide, Mithra Derakshan talked about her experience following the Woolsey Fire.

“I saw places that were lush and green turned to a complete moonscape, nothing there,” Derakshan stated. “In some places it was just ashes for thousands and thousands and thousands of acres.”

However, Derakshan explained the environmental rebound following the destruction.

“I got to see how quickly life came back. So, eight days after the fire, eight days of us being out of work, we started coming back to the park and looking and immediately we were seeing yuccas resprouting,” Derakshan said. “We were seeing soap plant, that was one of the first things, ceanothus small sprouts everywhere.”

The shrubs native to the Santa Monica Mountains can deal with the massive fires that come through, but only infrequently.

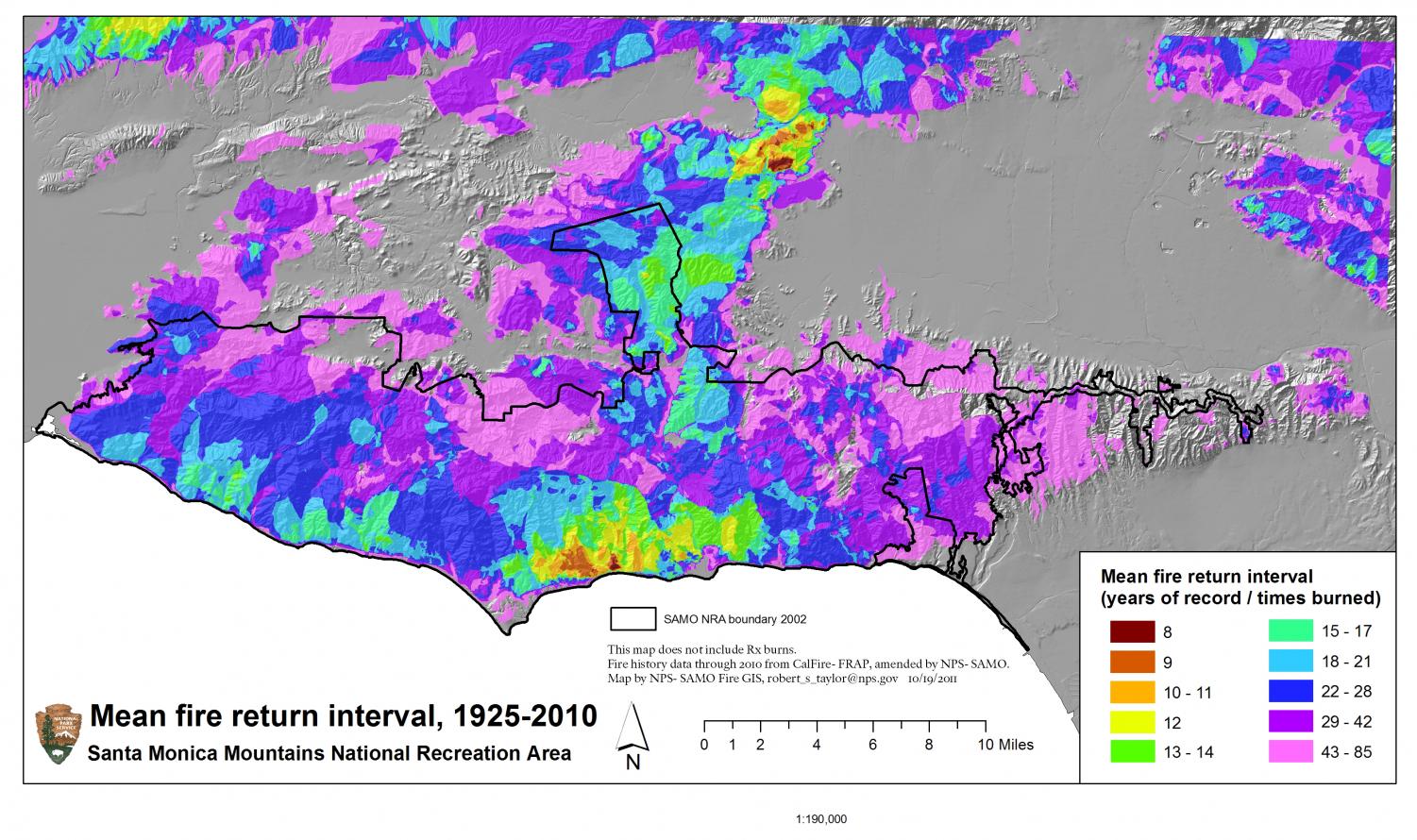

The park service estimates that wildfires should naturally occur about every 70 to 100 years, but instead wildfires are returning, on average, every 28 years. During the presentation, Witter displayed maps, assembled using data from 1925-2018, which showed that fires are actually happening about every 20 years in large swaths of the mountains.

The issue with more frequent fires is that they wipe out seeder shrubs and do not allow sprouter shrubs the opportunity to spread. When fires occur too frequently, seeder shrubs can’t build up the seed banks necessary for populations to bounce back, while sprouter shrubs don’t have time to spread and produce any new plants.

That said, while these populations are under stress, there are still things people can do to help. Park Guide Derakshan emphasized the need to be careful and let the environment recover after fires.

Derakshan stated, “I think it’s really important, after a fire happens, to be careful coming back into those zones, because they are already highly damaged. When you’re going to visit the parks, it’s really important to stay on the trails. It’s really important not to pick plants and pick flowers, even though they’re so beautiful.”

Park aide for California State Parks, Kim Bott echoed this advice as well. Emphasizing that the best thing people can do to help the local environment is to stick to the established trails.

“… If you’re going into hazardous areas that were burned and you want to go see, but you’re trampling on these areas, you’re preventing those plants and things from coming back,” Bott said. “So, just staying away from burned areas is probably the best thing to do.”

To visit the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and see the native landscape first hand, information is available online.