In America, it is customary to live a fast-paced existence that resembles an “on-the-go” lifestyle. I know I am guilty of this routine, but I get it; people have places to go and people to see. We become consumed by the things we take for granted; like where we come from or the sacrifices some people have to make to survive in this world.

I commute from Oxnard College to Moorpark College almost every day of the week, passing scenic California State Route 23 and 118, never really noticing my environment. On one particular day however, I sat in the passenger seat of my own car, only to experience one of the most humbling days of my life.

The colorful strawberry fields of Oxnard, Ca. that have decorated the city for centuries, have hundreds of agricultural workers tending to the fields in hopes of making a decent living. But as colorful as these fields may be, no one really ever takes the time to consider the hardships that field workers endure to be able to provide for their families.

As a first generation American from Mexican immigrant parents, I know firsthand what it means to make sacrifices and struggle just to stay afloat.

Despite my own personal struggles, I can admit that I have never worked a day, let alone a few hours, in any agricultural fields. I am almost certain that a large portion of our community has not either.

So, I ventured down to Pleasant Valley Road pass in Oxnard and set my eyes on a triangle field, ripe with growing strawberries. Jose Barrera, the Field Supervisor from Michoacán, Mexico, oversees this particular section.

“The most difficult part about doing this job is the actual picking,” said Barrera. “The majority of the workers that come here do work hard and put in the effort, but I have had people quit.”

According to Barrera, the harvesting period now lasts the entire year, when before it was just seasonal.

Barrera allowed me the opportunity to be a part of their team for a day, in hopes of getting experience in not only the picking techniques, but also, the labor that goes into the craft and the motivations that lead people to do this job.

I was humbled by the opportunity, but I quickly realized how physically demanding this day was going to be. Nonetheless, I prepared for the beginning of my day as the workers would.

I woke up at 5:30 a.m. to shower, get dressed and make my lunch. By 7:15 a.m. I was ready to start my day as a field worker. As I walked down the plank of dirt road to meet my supervisor for the day, all I could think about was how well I was going to be received in this environment.

Nervously, I approached the “Surquero,” which is the Line manager, to report for duty. He walked me over to one of the rows and taught me the basics in a 5-minute rundown. Luckily, I caught on quick.

Seconds later, he partnered me up with Armando Morales-Barrera, a 35-year old field worker from Michoacán, Mexico, who has been picking the fields for approximately 6 years.

“The hardest part about doing this job is the physical aspect,” said Morales-Barrera. “When I came here, I didn’t have a choice but to work the strawberry fields because I didn’t have the resources that I needed for a better job.”

Morales –Barrera and I worked as a team. As I picked the ripe strawberries, he enclosed them together neatly in their packaging. Eight small strawberry packages fit into a carton that was then taken to “La Contadora”, or “The Counter.”

Esperanza Ramirez, a 29-year-old field worker from Tlascala, Mexico, works as “The Counter.” She is responsible for checking the packaged strawberries for any discrepancies like mold, maturity and fullness.

“Make sure your next batch is a little fuller,” said Ramirez after checking the carton that I had given her to inspect.

This was just the third carton that I had filled, but I continued pressing forward. My partner, Morales-Barrera was incredibly encouraging and helped me keep my pace.

After two hours and 6 boxes later, my lower back was about to collapse. The blisters on the bottom of my feet were about to give way. The sun beamed on me as if it were out to get me and I grew thirstier by the minute and the treacherous mud lines were only keeping me from maintaining my balance.

I looked at my partner with tremendous respect and asked, “How do you all do it out here?”

“It’s all about making it through one day at a time,” said Morales-Barrera. “If we don’t talk to each other or help each other along, we won’t make it out here.”

The sounds of singing, music playing from small radios clipped to their pants and friendly chatter echoed in the field, as they try to get through their day and keep their spirits up high.

Most of the fieldworkers completely encase themselves with long-sleeve attire, hooded sweaters, hats, bandanas and beanies in order to keep the sun from striking.

“Most of us have permanent tans,” said Morales-Barrera. “The weather is what makes this job that much harder.”

Once lunch time came around, I had a few minutes to talk with some of the workers and get their perspective on what motivates them to do their job.

“I work hard every day to earn a living because for me, it’s a necessity,” said Ramirez. “This is definitely a sacrifice that we have to make to be able to prosper and put food on the table. I wouldn’t want my children to have to work in the field like I do.”

Ramirez left her two children behind in Tlascala with their grandparents, so that she could come to the U.S. and earn a better living for them. She hopes to return to Tlascala one day to reunite with her 11-year-old son, Julio Cahuantzi and her 6-year-old daughter, Monica Cahuantzi.

Rufino Mendoza, a 59-year-old field worker from Oaxaca, Mexico, explained his experiences since arriving in the U.S. and working in Oxnard, Fresno and Oregon. He is the oldest worker in this particular field area that continues to work through rigorous labor to help provide for his family.

“I came back from Oregon to be with my kids so that we can support each other in these hard times,” said Mendoza. “The labor is hard but unfortunately we have to endure this. I am just thankful that we have a job to sustain ourselves with.”

As I conversed with the workers, I got a chance to realize how hard working they truly are, as well as what motivates them to endure such a task. I can honestly say that I have developed an enormous amount of respect for all fieldworkers in whatever capacity they work in.

What I admired the most is their camaraderie; they are all united by a common goal. It’s such an incredible sight.

As I began my journey full of energy and focus, I ended it early full of exhaustion and back ache.

Although these people may not always be appreciated or recognized, we must acknowledge their hard work, as well as their hunger to live.

“It’s hard to integrate within our society because many people don’t see us as part of their community, but we are here trying to survive and work hard to feed our families, just like any other human being would try to do for their own family,” said Mendoza.

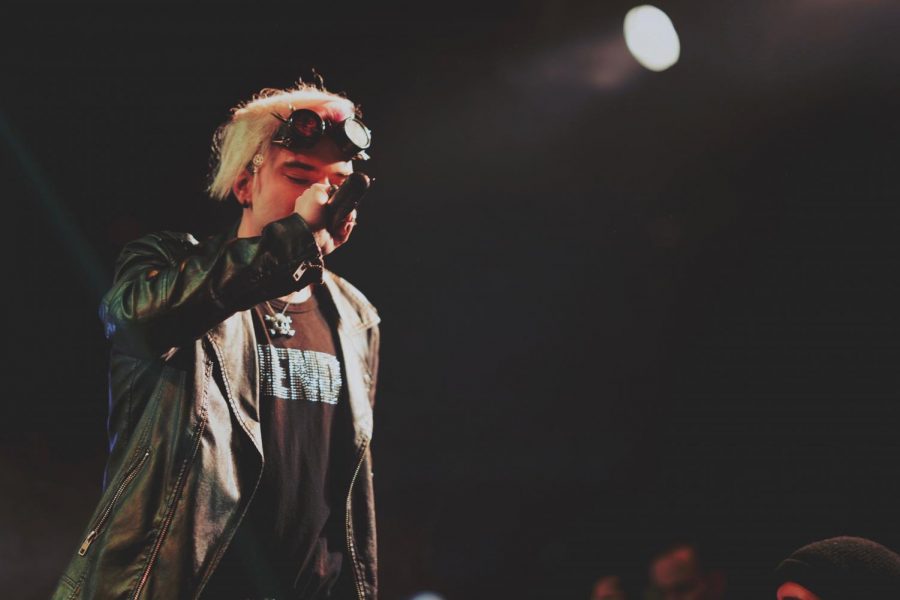

Fieldworkers work hard to make a decent living and provide for the families. (Photo by Oscar Machuca)

Monica Valencia takes a break under the shade, contemplating returning back to picking strawberries. (Photo by Oscar Machuca)