Moorpark students get practical experience at world-famous observatory

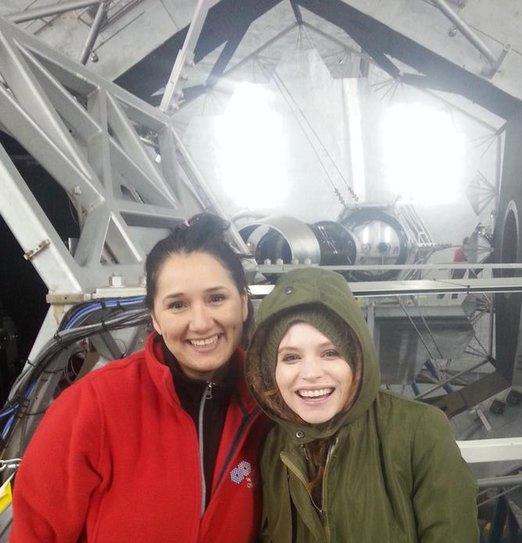

Professor Farisa Morales and Sandy Moak, astrophysics major, in front of the Keck telescope’s ten-meter mirror. Photo credit Justin Bracks.

April 22, 2016

Atop the summit of the highest peak in Hawaii, Moorpark College professor Farisa Morales and seven of her students were hunting for new planets within the galaxy.

“We spent two nights in W.M. Keck Observatory headquarters…to confirm the presence of 15 candidate sub-stellar companions around 13 stars,” said Shaurya Singh, 20, electrical engineering major. “In simple words, [we] were finding a planet.”

The group went to the world famous observatory at the summit of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and the highest point in Hawaii, to make use of the two most scientifically productive telescopes on earth, according to keckobservatory.org. Using a technique called direct imaging, they hoped to identify objects orbiting distant stars, said Morales.

“Dr. Morales’ research has to do with studying exoplanets via direct imaging,” said Justin Bracks, physics major. “Put simply, the technique involves placing a semi permeable light block in front of the actual star in the field of view of the telescope. By clever positioning/time-lapsed rotation of very powerful telescopes, Dr. Morales and her colleagues can painstakingly pull the visage of the planet out of the overwhelming glow of the host star.”

What Bracks is referring to is called a coronagraph. It’s like a filter that can be positioned over the lens to block out the bright light of the star so the companions orbiting it can be seen, said Morales.

“This is kind of like blocking out the moon with your thumb on a clear night and waiting for the stars to appear around it,” said Bracks.

The coronagraph is one of the key components necessary for the direct imaging technique to work, said Morales.

Another requirement for direct imaging is adaptive optics. Adaptive optics involves using a deformable mirror to sharpen the focus of the image. It then changes shape to compensate for the distortions of the image, said Morales.

Morales had gone to Keck several years ago and made initial observations for this project. She took images of candidate stars and found what appeared to be objects in their orbit. But because those objects just appear as points of light, they could actually be stars in the background that only appear to be objects in orbit.

To confirm the earlier findings, Morales and her team went back to look at those same stars. They were looking for those objects in the same proximity to the stars, which would mean they discovered new planets.

The group spent several nights at Keck making observations and collecting data.

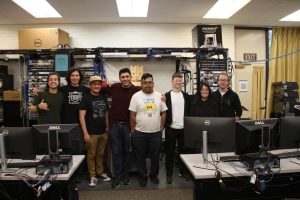

“The first two nights we were doing the observations at the observatory headquarters were some of the best memories of my adult life,” said Rebecca Henry, 20, student. “Dr. Morales and all seven of us took turns doing data entry both electronically and on paper and we all had the chance to drive the Keck II.”

Direct imaging is the newest technique being used to search for planets. The first time direct imaging was used to discover a new planet was in 2008, said Morales.

It will take time to comb through all the data and images the group collected, to see what they really found. Whether they discovered new planets or not, the experience was a worthwhile one for the students involved.

“I feel that I had a front row seat to some premier scientific exploration,” said Sandy Moak, 25, astrophysics major. “I wouldn’t have been able to get this kind of experience in any classroom, nor would I have been able to work closely with mentors and peers the way I did. I feel that I am even more confident about my choice to enter the field of astronomy and astrophysics, and I have much more context for the theory and research that I read about now.”